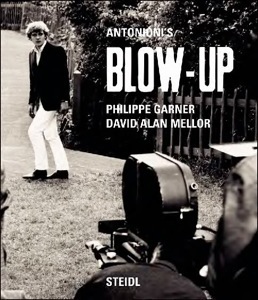

“The first comprehensive study of this cinematic masterpiece – a

fascinating analysis of the film’s central theme of photography, and an

insightful account of the fashion and art scene of mid-1960s London in

which the film is set.”

You know that we like to pursue the talk here at 160grams; our last

issue being about cinema, we could not have missed Steidl’s latest

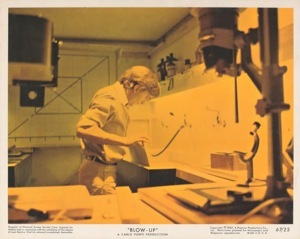

gem. Blow-Up (1966), a film often mentioned in the magazine, is one of

those iconic, sublime and very intellectual films that seldom find

publications that go beyond its superficial message. Luckily,

Antonioni’s Blow-Up is such a publication. It is a spectacular table-

book, containing countless vintage prints, stunning on-set stills and an

extensive amount of artworks and documents of the time, but it is also

a very serious study of the film through two very insightful essays.

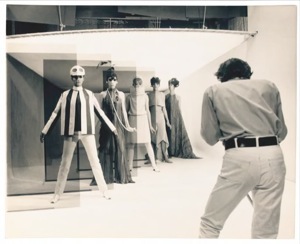

The first essay, by Philippe Garner, is called “Fleeting images:

photographers, models and the media – London, 1966” and brings

back to life the time of Bailey, Donovan and Duffy, of Veruschka’s

Swinging London, of the Modernist and Brutalist movements as well as

the rise of Pop. What Garneralso underlines is the thorough research

that Antonioni went through to prepare Blow-Up – surrounding himself

with contemporary British artists, such as Don McCullin, who shot the

photos shot by Thomas (the photographer and protagonist) in the film,

and painter Ian Stephenson, whose works are displayed in the film.

David Alan Mellor’s “Fragments of an unknowable whole:

Michelangelo’s Antonioni’s incorproration of contemporary visualities –

London, 1966” focuses on the relationship between Antonioni’s visual

language and British visual culture. As often with Antonioni, his films

are more than cinema: inBlow-Up especially, film is fused with

photography and painting. If in his previous and first Technicolor

film Deserto Rosso (1964), he used the visual vocabulary of

metaphysical artists and of Arte Povera, he turns towards

Rauschenberg, Richard Hamilton and Ian Stephenson for Blow-

Up. Pop Art and Swinging London mingle in a world of fashion,

appearances, photography and “mutability of evidence”. Considered

the only informal artist of cinema, Antonioni transforms the theme of

destruction of Deserto Rosso into the theme of destructive reproduction

in Blow-Up. Polysemic confusions between reality and imaginary are

the core of Blow-Up; the enlargement of the photographs leads to

mysterious, abstract and grainy canvases that belong to the world of

dream more than to that of reality.

Tate Britain; Ian Stephenson, Quadrama IV, 1969

Assheton Gorton reified the horizontal planes of Maryon Park – the

grass and paths –, lending a hyper-real aspect by adding green and

black paint to these surfaces, just as he added blackness to the tarmac

of the street outside Thomas’s studio. This process paralleled Boyle

and Hill’s taking of horizontal metropolitan ground, and isolating it as

hallucinatory. In such ways London, underfoot, artificially layered,

activated and pigmented, assumed a fascinating extra chromatic

weight and density.”

Antonioni also painted his own sets – the grass of Maryon Park has

been covered with green and black paint to make it look more real. The

director used what he called “colore mentale”, paradoxically over

painting reality instead of denying it. Thus not only the images within

the film, but the images of the film itself are artificially recreated to fit a

theatrical world that perfectly represents the absurdity of a fashion

photographer’s vision.

Mellor describes Maryon Park as a “theatrebox” setting, a parallel

universe of the unstable and the factitious. He also points out how

Antonioni followed the events of his time and the photographic

reproductions of Kennedy’s assassination especially: these remind us

of the relationship between photography and show during the Sixties.

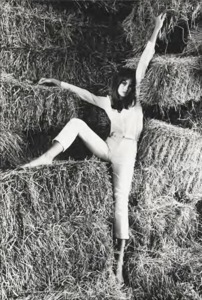

Theatricality in Blow-Up is omnipresent, with pantomimes and

carnivalesque figures of protesting students, models transformed into

dummies and robots, mannequins ever-performing through their use of

drugs. Theatre, music, film, photography, art and death are subtly

united in a film that is both the quasi-photographic witness of its era

and a sum of the works of art of its period at the same time.

Finally, Antonioni’s Blow-Up gives justice to the important and often

forgotten roles of Antonioni’s art director (Assheton Gorton) and

producer (Pierre Rouve), and to some themes that go beyond the usual

readings of Blow-Up, such as the Christian imagery mixed with a

metaphysical philosophy and the park as an interrupted Arcadia – not

only the setting of a mysterious event.

Park, Greenwich, February 2011 (photo Isa Jakob) – even nowadays,

despite the absence of the fences, the park is as metaphysical and out

of time as in Antonioni’s and Thomas’ time.

Images and preview of the book courtesy of Poppy Melzack; for more

informations, visit Steidl’s page (the book, freshly published, has 113

pages, hardcover with dustjacket, and measures 24.5 cm x 28.6 cm).

In case you have never seen the film, we highly recommend you to!